Business is a noble pursuit and necessary to sustain life.

But

LOVE

is what we stay alive for.

The bison, or American buffalo, is a massive horned woolly ruminant native to North America – a descendant of one of the great Pleistocene giants that wandered across the Bering Strait land bridge during the last Ice Age. Today, the bison can be divided into two subspecies: the plains bison (Bison bison bison), and the larger, more northerly wood buffalo (Bison bison athabascae).

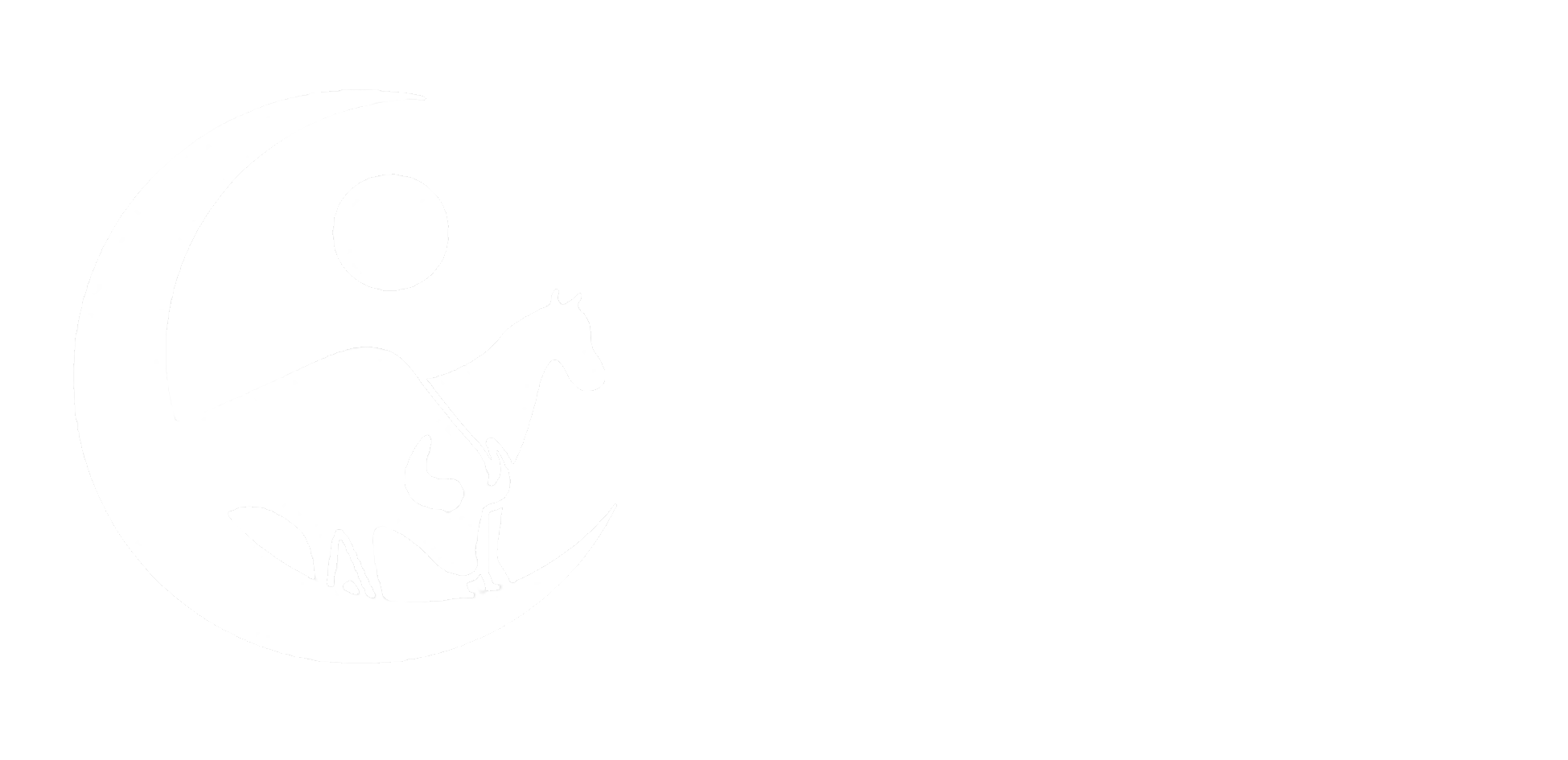

Before the 19th century, millions of plains bison roamed the grasslands of North America in enormous herds. For millennia, the Plains Indians of what is now Canada and the United States subsisted almost entirely upon these so-called “Kings of the Prairie”, using their meat and marrow for sustenance, their hides for shelter and clothing, their bones for tools, and their dung for fuel. One of the most effective methods by which the Plains Indians hunted this animal involved natural cliffs, or “buffalo jumps”. During such hunting operations, a band would build two long funnel-like drive lanes extending from the edge of the cliff to the open prairie. These drive lanes were composed of hundreds of stone cairns, each built several meters apart from one another, often augmented with dirt, buffalo dung, tree boughs and sagebrush.

Over a period of several days, specialized hunters well-versed in animal behaviour would disguise themselves as juvenile bison and prairie wolves and lure a buffalo herd into the drive lanes. When the majority of the herd was within the lanes, hunters who had concealed themselves behind the cairns would suddenly leap out from their hiding places, screaming and waving buffalo robes.

At the same time, the hunter disguised as a juvenile buffalo would “flee” towards the cliff, prompting the startled herd to follow him. Just before he reached the cliff’s edge, the “buffalo runner”, as this elite hunter was called, would retreat to safety behind the line of the cairns. If all went as planned, the entire herd would stampede off the cliff to its death, unable to stop on account of its massive momentum. Hunters waiting below would finish off wounded and crippled buffalo with spears, bows and arrows, and clubs.

Although Plains Indian bands sometimes managed to wipe out entire herds during these annual buffalo hunts – believing, as many of them did, that any bison which managed to escape the slaughter would disclose the secret of the hunt to its woolly compatriots – the bison population on the Great Plains and Canadian prairies remained extremely robust.

The Disappearance of Buffalo

In the late 1700s, the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company, two rival fur trading enterprises, expanded westward onto the eastern edge of the Canadian prairies. Soon, that area, comprising what is now Manitoba and North Dakota became populated by bands of Metis – the progeny of French and Scottish fur traders and First Nations women.

Like the western counterparts of their maternal ancestors, the Metis were excellent buffalo hunters. Instead of driving their prey off cliffs or herding them into buffalo pounds, however, Metis hunters shot them with muskets from horseback. In order to provision their voyageurs for their long voyages along the waterways of Rupert’s Land, the fur trading companies began purchasing huge quantities of pemmican from the Metis, pemmican being a nutritious travel food composed of equal parts dried pulverized buffalo meat and rendered buffalo fat, on which many of the Plains Indians had subsisted since time immemorial. The pemmican trade quickly grew into a thriving industry which slowly took its toll on the bison population on the eastern prairies.

Around this time, the First Nations of the western Canadian prairies were introduced to the horse, an Old World animal that had slowly worked its way up the continent since its introduction to the Americas by Spanish conquistadors. Many of the Plains Indians quickly became proficient horsemen, and their way of life changed completely. With these new equine vehicles, the Plains Indians were able to hunt more quickly and efficiently than ever before. The fruitful buffalo hunts that ensued allowed them to increase their population, resulting in an imperceptible yet very real decrease in that of the plains bison.

In the mid-1800s, the American Fur Company, a Yankee rival of the Hudson’s Bay Company (the latter having absorbed the North West Company in 1821), expanded up the Missouri River, taking the fur trade to the Great Plains. Certain Plains Indians tribes began to deliver buffalo robes to American traders in exchange for Western goods. One of the items the Plains Indians acquired through this trade were firearms, which allowed them to hunt the buffalo with even greater ease. And thus, the bison population on the Great Plains was further curtailed.

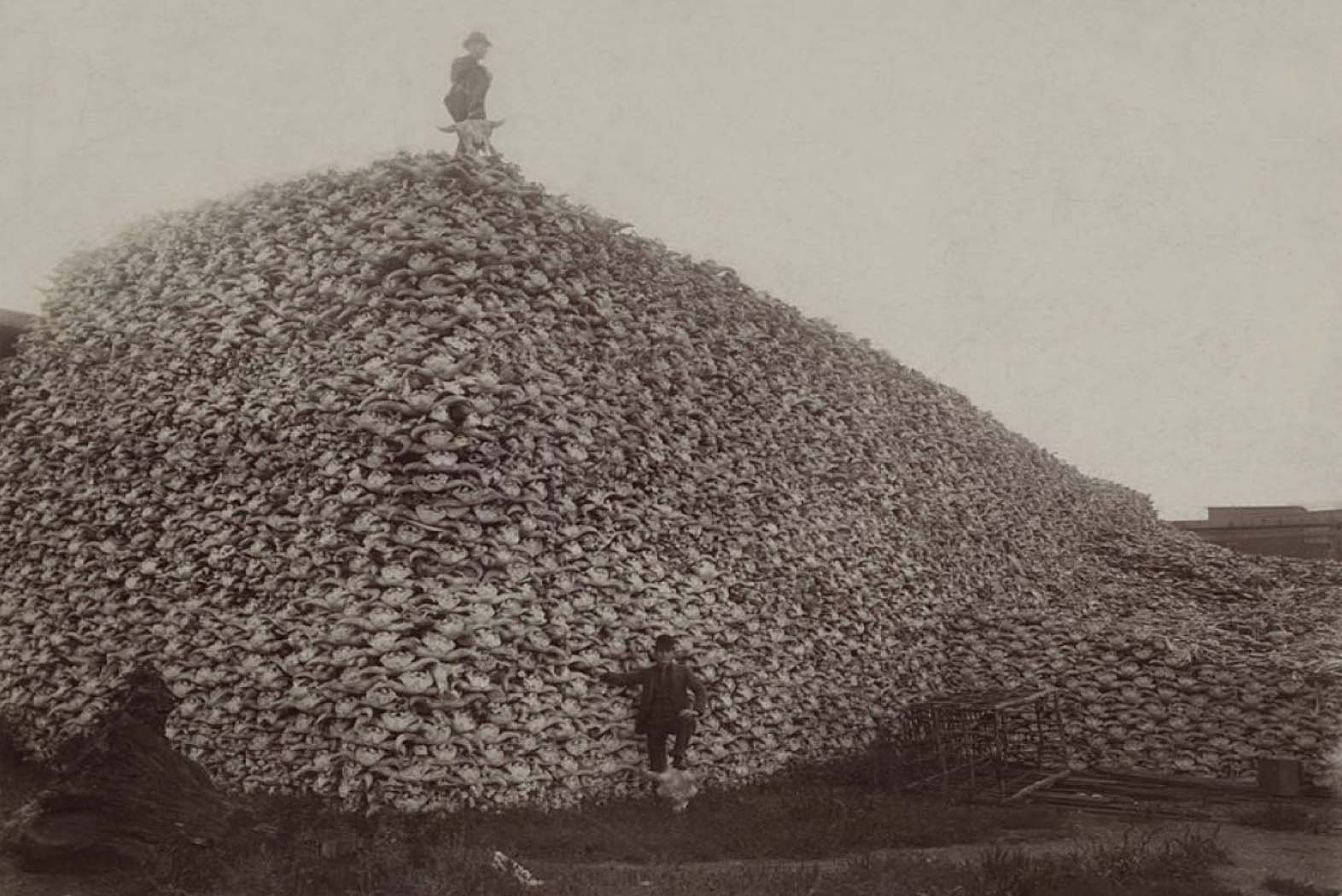

In the early 1870’s, a cheap process for tanning hides was developed in Europe. Almost overnight, demand for buffalo hides, which could be transformed into leather for militaries and durable industrial belts for factories, exploded. Unlike buffalo robes, which could only be harvested in the winter when bison coats were thickest, buffalo hides intended for use as leather could be harvested at any time of the year. Soon, hordes of big game hunters poured onto the Great Plains from the eastern States via the Union Pacific Railroad and began slaughtering bison by the millions for their hides alone. The already-dwindling buffalo population began to plummet at an alarming rate.

The final nail in the coffin of this monarch of the plains was forged at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, which saw the U.S. Army’s 7th Cavalry Regiment wiped out by Sioux warriors under the command of Chief Sitting Bull. Following this defeat, high-ranking U.S. Army officers routinely sponsored and outfitted civilian hunting expeditions, hoping to drive the buffalo to extinction, thereby forcing the Sioux and other uncooperative Indian tribes to settle onto reserves without having to engage them in battle.

Although the U.S. Army did not have an “official policy” aimed at the destruction of the buffalo, as popular history sometimes contends, its top brass were manifestly pleased to see buffalo hunters doing “more… to settle the vexed Indian question than the entire regular Army has in the last 40 years,” as U.S. Army General Philip Sheridan put it.

(Cited from https://www.mysteriesofcanada.com/alberta/how-canada-saved-the-buffalo/)